> But politically, I was not much aware, especially in the early years, because of the obfuscation and invisibilization of the people's history in Kashmir.

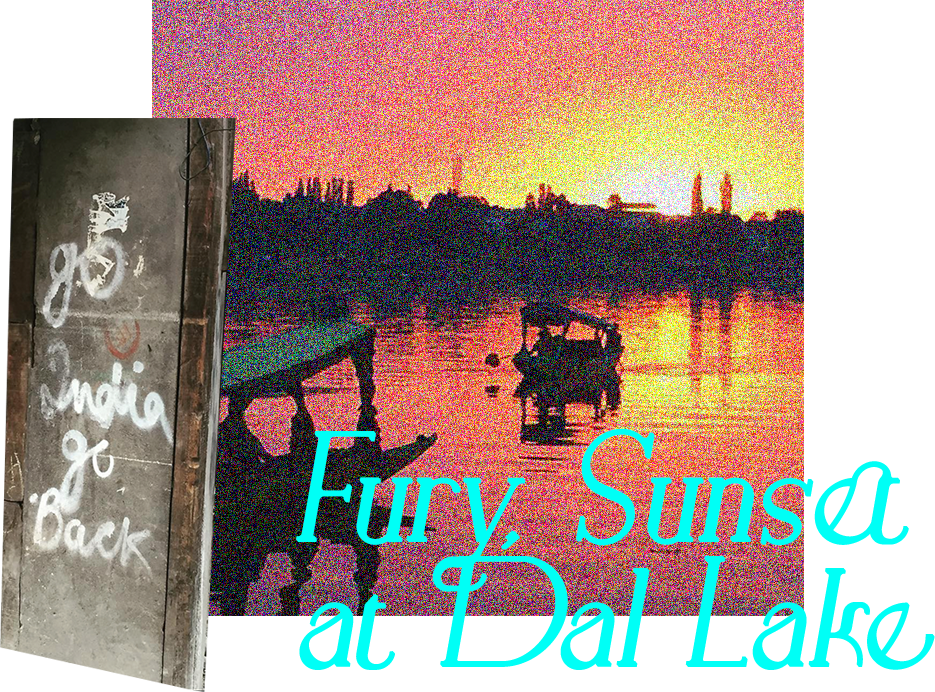

I GREW UP in the foothills of a mountain in Kashmir. This mountain has two names. One name is Shankaracharya and the other one is Takht-i-Sulaiman, meaning the throne of Solomon. I was a kid, so I wasn't really paying attention that it was referred to by two names, or that these were two different names coming from two different religious streams and histories. I lived with my maternal grandfather and he was the one who raised me. Growing up, I kind of knew personally who I was and what my family wanted me to do.

Editor's Note:

This interview was recorded in July 2021, and co-edited with Ather in September 2021.

Ather is a political anthropologist, so she has grounded her story in socio-political context. As you read, click on the blue underlined text to access the reference.

she/her

I was very young to make sense of politics, but one of my earliest memories that shaped my political subjectivity is the hanging of Maqbool Bhat in the early eighties. Bhat is considered to be the father of the Kashmiri independence movement, and he was hanged by the Indian government. His name stuck in my mind. I would ask questions about him and I would get different answers. He had been punished in Pakistan. He was a fierce Kashmiri nationalist. After being jailed in India he was hanged. His body is interred in Tihar jail. In that sense even his dead body is jailed. Growing up there wasn't a lot of literature on him.

Another memory that shaped my political subjectivity, maybe even before Bhat’s hanging, is the passing of Sheikh Abdullah. As a young kid I was taken to see the funeral by my family. I recall watching the funeral procession from a tall building. Looking at the corpse, I recall thinking his face was yellow. I do not know if this memory is correct since Muslims usually cover the face of a corpse. There were thousands of people in the procession. I remember feeling a lot of tension, not only because people were crying. Abdullah was very well-loved by a section of people but many in the crowd I was in were calling him gaddar or a traitor. I recall this word stuck in my mind, not knowing what it meant. For a long time I thought the people were saying “gadda” meaning donkey. The “gaddar” word was used in reference to his capitulation to India.

ANOTHER MEMORY IN the early 90s was when I was waiting for a friend of mine, who had promised that we would meet in Lal Chowk, which is the center of Srinagar. She was a Kashmiri Pandit and I'm a Kashmiri Muslim. Until that point in time, I didn't really think about the difference of religion as pivotal or being a barrier. Our meeting would be the first time we would hang out outside school and without being chaperoned. I got there at 11 am and waited until 2 pm…she didn’t come. So then when I went home, I tried to call her, but I learned nothing. After some searching, I came to know she had migrated. Majority of Kashmiri Pandits in the early 90s migrated from Kashmir. Most were scared of the militancy. Majority of the Pandits sided with India, and a Kashmiri resistance which was dual centered around Independence and accession to Pakistan was not aligned to their political vision with a Hindu India.

Barring some exceptions, most Pandits have always supported Indian rule. In an atmosphere of distrust and fear, there were selective killings of prominent Kashmiri personalities who supported India; this was from both the Muslim and Pandit community. Scholars note that the selective killings by the militants were based on politics and not religion, but many Pandits accused the resistance or the Tehreek for being communal. Muslims blame the political violence and the perception of fear, which was amplified by the government that facilitated the migration. Despite call for the same, the government of India thus far has not initiated any inquiry into the killings despite clamor from both the Pandit as well as the Muslim community.

ANOTHER SAD INCIDENT was when a batchmate in high school was killed. He was walking just a few paces behind me. While I crossed the road, he probably was lagging behind and got caught in a crossfire. His killing changed something fundamental for me, as did the overall political crisis and extreme human rights violations that Indian military occupation wrecked on Kashmiris. All these incidents and events, the rise of armed resistance, grave human rights abuses by the Indian military and other forces shaped my political subjectivity. I thought, why is this happening? And there was no coherent explanation. I asked an uncle of mine, why is this happening? And he said, these are the questions that you have to find answers for yourself.

He said:

They

have

put

padlocks

on

our lips.

ONE OF THE MOST vivid memories I have is that of a mother who would sit on the porch of her house, asking passersby if they have seen her son or if he is coming. I slowly realized that it was not just a routine query but that her son had been forcibly disappeared in custody by the Indian army. The mother had lost her mental balance. Later I began to witness Parveena Ahanger, the mother who co-founded the human rights group known as the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (or the APDP).

The immense violation of people’s rights in response to their demands made me think about the kind of political system we were living in. I had studied about democracy in school but what I saw around me made me start thinking, if they call it a democracy, how can people be disappeared like that? How can we have so much militarization? When Kashmiris speak about there being “peace” before 1989, or the ideals of democracy being in place, that really needs to be unpacked, because this nostalgia is sometimes misrepresented in Indian narratives.

When Kashmiris say there was peace before 1989, they are not saying that there was an absence of Indian military aggression before 1989. Or that Kashmiris were not asking for our political rights. We have been coerced every decade. In every decade, our movement was criminalized further. There has never been peace in Kashmir. Before 1989, there was an absence of brazen and direct militarization, but the militarization had started in 1947 itself. In fact, I remember being in school when these things started unfolding. I would count the number of bullets I heard and keep a log of it. I don't know what that meant to my teenage brain. I guess it kind of told me the intensity of the fight that was going on.

As a political anthropologist, enforced disappearances allowed understanding and explaining the Kashmir dispute specifically through Kashmiri women’s eyes. It gave me a chance to look at Kashmir’s history, talk about weaponization of democracy and also bring Kashmiri women into the limelight. Not that we are glorifying their desperation and glorifying the human rights violations that are pushing them to join mainstream life. We’re talking about how Kashmiri women have always shown their agency. Women have always worked side by side with men. And also, Kashmiri society is just as unique as any other society, it’s as patriarchal as any other society. It's not uniquely patriarchal as India has been portraying it to be.

I MOVED TO London as a journalist for BBC in 2001, but realized that as a journalist I was not able to read and write freely. I went back to Kashmir. I had qualified for Kashmir Administrative Service (KAS) and was posted as a Community Development Officer. I felt it was a perfect amalgam, I could serve marginalized communities, and pursue writing as well. But bureaucracy in Kashmir is a doubly convoluted beast. Towards the end of my KAS run, I self-diagnosed myself with the Kashmiri bureaucratic schizophrenia. This ailment begins when you are doing what you think is just a job that includes routine challenges of civil services, but you steadily become aware of how strategic your role is in strengthening the Indian apparatus. At this juncture, your positionality becomes awash in moral greys, which, depending on your life options, fuel either your flight or petrification.

Afterhours, I would find some kindred colleagues equally stuck in the schizophrenic funk as they took turns justifying their position in the services. Some said it was just a job to meet family obligations; others asserted that if it were not for them, people would lack essential services. A few irrepressible ones thought they would change the system from within. Some loved the status the office brought with it. Others felt their presence was crucial to protect Kashmir's regional interests. A few bragged they were becoming privy to classified information which helped them understand the Indian machinations better; to what end, it baffles me till today. Also while most wanted laurels matching their competence, initially at least, their default mode was resistance to the Indian ministrations as much as any other non-civil servant Kashmiri.

I found myself having to pay obeisance to higher up bureaucrats and the local ministers. And the ministers are so beholden to India. I also felt that as a Kashmiri, I had already been feeling subjugation actively and brazenly since 1989. I just could not do it. So I decided I would leave for higher studies. But you really can't study Kashmir in Kashmir. Because you can’t really speak the way you want to speak for Kashmir, in Kashmir. You have to leave. I would never have wanted to leave like the way I did, but I had to put this distance. If I could have, I would have been doing Kashmir work in Kashmir and I would have been with my family. But I had to leave.

And what complicates this further is that after 18+ years of studying and being focused on Kashmir, I’ve come to realize that I'm in someone else's nightmare. How is it possible that I can come to America, trying to study Kashmir, write about Kashmir, and then be part of the settler colonialism perpetuated on the First Nations here? The US is a settler colonial state which the patina of “democracy” had hidden, and in the recent years, this irony of my positionality is sinking in. Our fight as Kashmiris is against India, and it is also against the structure of imperialism and neocolonialism activated by the weaponization of neoliberal democracy.

EARLY IN MY TIME in the US, I was trying to find a voice for myself because all I had seen as a Kashmiri was Indian authors, Indian writers, Indian researchers – even as they visited Kashmir as friends – me and my counterparts felt like we were under scrutiny. They would take my narrative, take it elsewhere, and make it their narrative. They would add stuff to it. When I’d talk to Indian feminists and then read the chapters that they would write after talking to me, they would demonize Kashmiri men and make Kashmiri women seem more desperate than let’s say Indian women. I would always say, where is the Kashmiri woman they witnessed? There's so much about Kashmiri women in the Indian narrative, but the Kashmiri woman who really thinks for herself, is agentive or has come a long way, she's mostly invisibilized. Kashmiri patrirachal structure is shown as uniquely violent and oppressive.

So now, how do Indians offer solidarity? That's very tricky. There are many academics and friends who I love, who are with you when you talk about human rights violations in Kashmir, but the moment you speak about the political dispute, they tune out because then they feel that their nation state is attacked. And if I was to be in solidarity with those people who are saying, only stop human rights violations, my own political loyalties will get diluted. Because I don't only want to stop human rights violations, I want the political dispute to end because human rights violations are occuring precisely because our political rights are annilated. It's not as if India just decides to kill Kashmiris. India is killing Kashmiris because they're seeking Azadi which is not palatable to India. So even when you get solidarity, it's a conditional solidarity, it's a selective solidarity, which means it's a shallow solidarity, which means there's no solidarity at all.

> I would never have wished this exilic condition, as Agha Shahid calls it, on anyone.

And now it's also getting more complicated because of the Hindu supremacist agenda, and Islamophobia is huge as well. India sees the work of Kashmiris like me as “intellectual terrorism.” In the last 74 years, the Indian hegemony on discourse on Kashmir – which has begun to wane, thank God – , obfuscated Kashmiri political demands to the point of criminalization and created ways to erase international attention and solidarity for Kashmir. Scholars have challenged India’s arguments, especially those that obfuscate Kashmir’s historical demand for a democratic sovereignty; that present Kashmir issue as Pakistan’s proxy war; or reduce it to the erroneous stereotype of “Islamic terrorism” and relegate it to a domestic law and order situation. India continues to spin Kashmiri resistance as “terrorism” and the onslaught on my work or that of my counterparts becomes a low hanging fruit.

AS FAR AS PAKISTAN is concerned, Kashmiris of all inclinations share an affective relation with Pakistan. That is non-negotiable. As for political goals, while the majority of Kashmiri Muslims seek independence, a strong section wants to accede to Pakistan. Most Kashmiri Muslims continue to share a deeply affective relation with Pakistan based on religious, spiritual, cultural and trade ties that predate the formation of what is now Pakistan and India. The breadth of this relationship is reflected in arguments the last Dogra king made when the Indian leaders were influencing him to join their union in 1947. He argued that Kashmir was fully dependent on the region that became Pakistan and was geographically contiguous as well. Kashmiris across the LoC continue to bear the brunt of brutal division of their homeland that separates families and valuable resources.

So as far as Pakistani solidarity in diaspora is concerned, as of today I think Kashmiris are now more confident in how to voice and seek their rights. In the last one decade and more so since 2019, Pakistanis in diaspora are giving Kashmiris the kind of solidarity Kashmiris need: which is, throwing their weight behind Kashmiris' right to choose their own political destiny.

WHEN I FIRST CAME to the US, there were a lot of Kashmiris already here, working for the Kashmir cause. They are senior people and they have faced different a geopolitical situation, which of course has changed and has not as well. In the early 2000's, the diaspora was sort of in flux because the Kashmiri resistance had entered a new phase. The militancy had ebbed, a second intifada which consisted of more grassroots resistance had set in, there was an urgency, and the road map was still evolving. On 5th August 2019, the Indian occupied Kashmir burst anew into the international conscience when India militarily and against its own constitution removed the region’s quasi-autonomous status.

In the early 2000’s, what was happening in Kashmir was this new policy called Healing Touch. A new party aided and abetted by the Indian government had formed and was said to be giving a “healing touch” to people. And by that, they meant that they were propagating a kind of soft autonomy, where movement across the Line of Control (LoC) would be made easier and the local government would take charge of its resources.

> On 5th August 2019 the Indian-occupied Kashmir burst anew into the international conscience when India militarily and against its own constitution removed the region's quasi-autonomous status.

As Kashmiris in the region were silenced, the diaspora and their allies were activated to garner support for the people long brutalized and pushed into the corner by Indian policies. August 2019 became another milestone when the issue of Kashmir resurged and re-internationalized. Countless voices, both Kashmiris and from their allies, across Europe, across the US, were able to come together, despite differences and seize the moment. And I think it also affected Kashmiris of all shades, class and inclinations. The carpet was pulled from under everyone’s feet. I must add that the autonomy under Article 370 was a symbol of Kashmir’s historical sovereignty and it served to underwrite the demand of self-determination by the Kashmiri people. Kashmiris were for the autonomy more to protect their territorial sovereignty and keep Indian settlers at bay, rather than any kind of loyalty to India.

I ALWAYS HAD this journalist side, but I’ve also always had a linkage with creative writing, literature and arts. It was my main love. In fact, I actually wanted to do my masters in fine arts, but I ended up in journalism because there was no writing program in Kashmir. And that has happened to a lot of Kashmiri students. I don't know if even now, the Kashmir University has a creative writing department. I founded the e-zine Kashmir Lit in 2008. I wanted it to be a platform for Kashmiris to write and be published. And these would be young Kashmiris who are not being heard and who don't have many avenues. It could be poetry. It could be fiction. I wanted to do something on an international level. Kashmir Lit also invites people from across the LoC to contribute. For the last 70 years, Kashmiris across the divide haven't really been on one platform together. And I'm not saying Kashmir Lit is unique in that. But that's been my focus, to bring voices from across the LoC, for them to write and create resonance with the political agony suffered by the other side. Recently, Kashmir Lit started a new series called Mulakaat Ganimat (meaning, meeting is a boon). This program aims to produce conversations with people who are serving the society through arts and politics.

WHEN I DIE, I want them to say that she spoke for Kashmir in the way Kashmiris want to be spoken of. With grace, honor and respect for their identity, resistance, and politics, with whatever tools she had: be it day-to-day living, academia, poetry, and small conversations with someone. The legacies people will leave are so small in front of the sufferings of the people. But we need to persist in not allowing hegemonic occupiers to erase us.

ATHER ZIA, PhD (she/her) is a political anthropologist, poet, short fiction writer, and columnist. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology and Gender Studies program at the University of Northern Colorado Greeley. Ather is the author of Resisting Disappearances: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir (June 2019) which won the 2020 Gloria Anzaldua Honorable Mention award, 2021 Public Anthropologist Award, and Advocate of the Year Award 2021. She has been featured in the Femilist 2021, a list of 100 women from the Global South working on critical issues. She is the co-editor of Can You Hear Kashmiri Women Speak (Women Unlimited 2020), Resisting Occupation in Kashmir (Upenn 2018) and A Desolation called Peace (Harper Collins, May 2019). She has published a poetry collection “The Frame” (1999) and another collection is forthcoming. In 2013 Ather’s ethnographic poetry on Kashmir has won an award from the Society for Humanistic Anthropology. She is the founder-editor of Kashmir Lit and is the co-founder of Critical Kashmir Studies Collective, an interdisciplinary network of scholars working on the Kashmir region.

Before 1947, Kashmiris lived under a monarch who was a Hindu. He was a tyrant and Kashmiris lived mostly in indentured slavery. The Dogra dynasty had paid money to the British in 1846 for Kashmir, so for the next hundred years, they were trying to recoup the investment. So as a result, the majority of the Kashmiri Muslims lived a hand-to-mouth existence. There were lots of droughts. There were plagues. And our sense of identity was embattled. Both during the Sikh rule and the Dogra rule, the majority of masjids were made in the stables, and Kashmiri Muslims were not allowed to pray.

In the early 20th century, Kashmiris begun getting education, especially at Aligarh Muslim University and also going to Lahore and Karachi. We started having access to newspapers. So Muslims in Kashmir were getting aware of the fact that they were being treated really badly, not just politically, but their religious freedom was also compromised. That’s when young leaders like Sheikh Abdullah came up, who led the fight against the Dogras. His party later on drafted the Naya Kashmir manifesto that was fashioned on the Communist Manifesto. Even though a Kashmiri nationalist, he essentially ended as a client politician and put his weight behind a coerced “integration” policy with India.

WITH REGARDS TO my Muslim identity, I didn't realize how lucky we were to be growing up in a place where at least something related to our identity had been resolved, and that was the acceptance of who Kashmiris were as Muslims. I might just be speaking for my own family. In Muslim households, there’s this joke: If you have a prayer mat and you keep it open, people say, oh, you kept the prayer mat open, now Satan is going to come and pray. Which is just a way of saying, roll up your mat. But it would bother my grandfather that people would say this, and he would respond:

Do you know there was a time not too long ago, when it was not so easy to unroll the prayer mat? So why do you keep asking me to roll it?

Before 1947, Kashmiris lived under a monarch who was a Hindu. He was a tyrant and Kashmiris lived mostly in indentured slavery. The Dogra dynasty had paid money to the British in 1846 for Kashmir, so for the next hundred years, they were trying to recoup the investment. So as a result, the majority of the Kashmiri Muslims lived a hand-to-mouth existence. There were lots of droughts. There were plagues. And our sense of identity was embattled. Both during the Sikh rule and the Dogra rule, the majority of masjids were made in the stables, and Kashmiri Muslims were not allowed to pray.

In the early 20th century, Kashmiris begun getting education, especially at Aligarh Muslim University and also going to Lahore and Karachi. We started having access to newspapers. So Muslims in Kashmir were getting aware of the fact that they were being treated really badly, not just politically, but their religious freedom was also compromised. That’s when young leaders like Sheikh Abdullah came up, who led the fight against the Dogras. His party later on drafted the Naya Kashmir manifesto that was fashioned on the Communist Manifesto. Even though a Kashmiri nationalist, he essentially ended as a client politician and put his weight behind a coerced “integration” policy with India.

WITH REGARDS TO my Muslim identity, I didn't realize how lucky we were to be growing up in a place where at least something related to our identity had been resolved, and that was the acceptance of who Kashmiris were as Muslims. I might just be speaking for my own family. In Muslim households, there’s this joke: If you have a prayer mat and you keep it open, people say, oh, you kept the prayer mat open, now Satan is going to come and pray. Which is just a way of saying, roll up your mat. But it would bother my grandfather that people would say this, and he would respond:

Do you know there was a time not too long ago, when it was not so easy to unroll the prayer mat? So why do you keep asking me to roll it?

Before 1947, Kashmiris lived under a monarch who was a Hindu. He was a tyrant and Kashmiris lived mostly in indentured slavery. The Dogra dynasty had paid money to the British in 1846 for Kashmir, so for the next hundred years, they were trying to recoup the investment. So as a result, the majority of the Kashmiri Muslims lived a hand-to-mouth existence. There were lots of droughts. There were plagues. And our sense of identity was embattled. Both during the Sikh rule and the Dogra rule, the majority of masjids were made in the stables, and Kashmiri Muslims were not allowed to pray.

In the early 20th century, Kashmiris begun getting education, especially at Aligarh Muslim University and also going to Lahore and Karachi. We started having access to newspapers. So Muslims in Kashmir were getting aware of the fact that they were being treated really badly, not just politically, but their religious freedom was also compromised. That’s when young leaders like Sheikh Abdullah came up, who led the fight against the Dogras. His party later on drafted the Naya Kashmir manifesto that was fashioned on the Communist Manifesto. Even though a Kashmiri nationalist, he essentially ended as a client politician and put his weight behind a coerced “integration” policy with India.

WITH REGARDS TO my Muslim identity, I didn't realize how lucky we were to be growing up in a place where at least something related to our identity had been resolved, and that was the acceptance of who Kashmiris were as Muslims. I might just be speaking for my own family. In Muslim households, there’s this joke: If you have a prayer mat and you keep it open, people say, oh, you kept the prayer mat open, now Satan is going to come and pray. Which is just a way of saying, roll up your mat. But it would bother my grandfather that people would say this, and he would respond:

Do you know there was a time not too long ago, when it was not so easy to unroll the prayer mat? So why do you keep asking me to roll it?